The culture industry, a concept introduced by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer (Adorno & Horkheimer, 1944), highlights how media manipulates people by making cultural products feel standardized and predictable. In today’s digital age, algorithms have taken this to another level, shaping what we see, hear, and consume online, and turning culture into a commodity even more than before.

In the past, traditional media like TV, radio, and movies were the main tools used to control trends and shape culture. With the internet, it seemed like independent creators could finally bypass big corporations and share their work freely. But now, tech giants like Google, Amazon, and Facebook act as new gatekeepers, using algorithms to decide what content gets seen (Van Dijck et al., 2018).

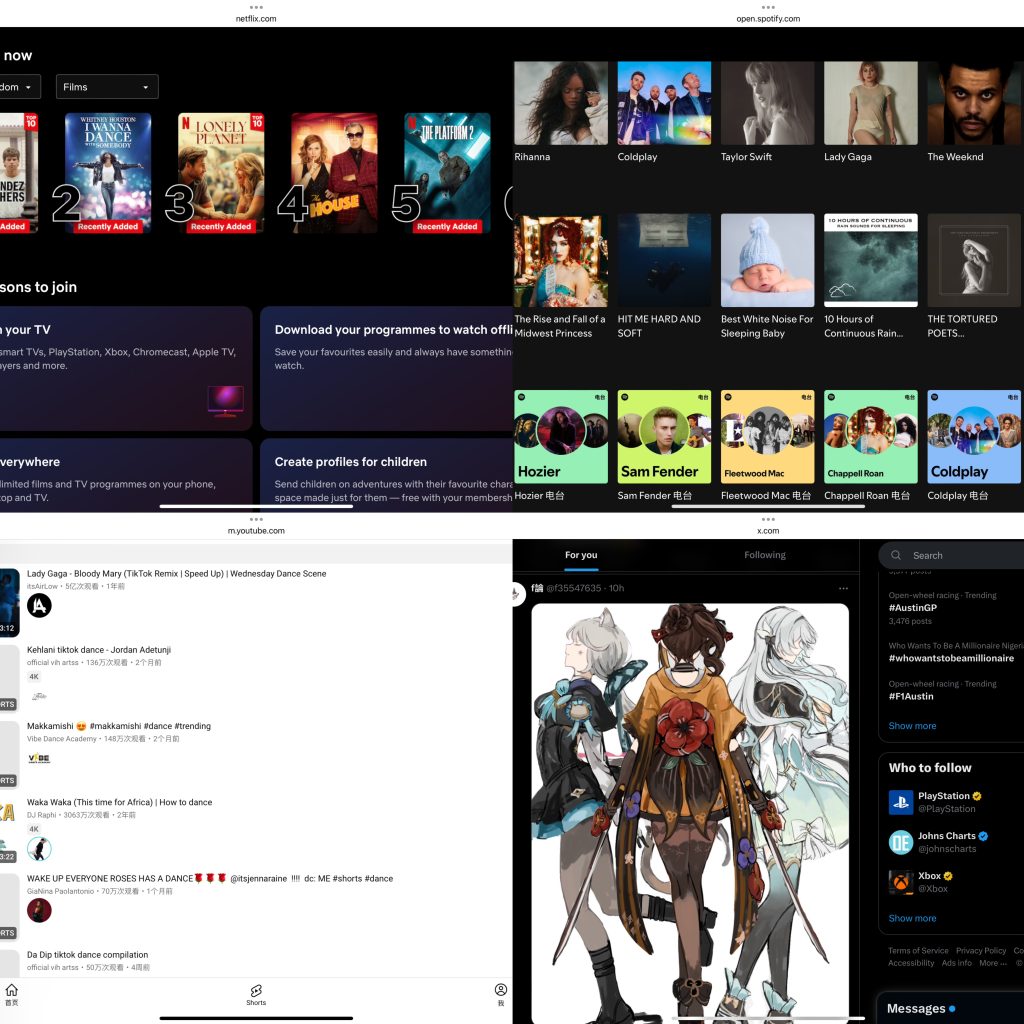

Platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Spotify claim to personalize content for users, but this often means showing the same type of stuff repeatedly (Pariser, 2011). For example, Spotify’s playlists push popular music, making it hard for niche or experimental artists to get noticed (Morris & Powers, 2015). Similarly, TikTok’s algorithm rewards short, catchy videos, which is great for trends but limits the variety of what’s shared and seen.

Another problem is how these platforms make money. They rely on ads and want to keep people engaged for as long as possible. This means creators often feel pressured to make content that fits what the algorithm favors, like viral dances or catchy slogans, instead of focusing on originality (Zuboff, 2019). Social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok encourage users to follow trends because that’s what gets the most likes, followers, and brand deals. Creativity can take a backseat to what works for the algorithm.

There are also ethical concerns. Algorithms are not transparent, which raises questions about bias. Often, marginalized creators struggle to get their voices heard if their content doesn’t align with what’s popular. Platforms like YouTube have also been accused of promoting controversial or misleading content because it gets clicks, even if it’s harmful (Noble, 2018).

However, not everyone is going along with this system. Many independent creators are turning to alternative platforms or crowdfunding sites like Patreon to stay independent. Grassroots movements and open-source platforms are working to give people more control over their content and how it’s shared (Gillespie, 2018). Supporting initiatives like Bandcamp or the Digital Public Library of America can also help promote diverse and creative content instead of just what’s trending.

In conclusion, the culture industry has evolved but remains relevant in understanding how media shapes society. By being aware of how algorithms influence what we see and consume, we can make better choices, support creativity, and push back against the dominance of mass production in the digital age.

Reference:

Adorno, Theodor, and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Stanford University Press, 1944.

Van Dijck, José, Thomas Poell, and Martijn de Waal. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Pariser, Eli. The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think. Penguin, 2011.

Morris, Jeremy Wade, and Devon Powers. “Control, Curation and Musical Experience in Streaming Music Services.” Creative Industries Journal, vol. 8, no. 2, 2015, pp. 106-122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2015.1090222.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs, 2019.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. NYU Press, 2018.

Gillespie, Tarleton. Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media. Yale University Press, 2018.