Manufacturing consent is a concept developed by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky to explain how powerful institutions shape public opinion by the ways in which information is selected, framed, and circulated. Rather than using overt propaganda, modern media works through subtler mechanisms such as repetition, selective emphasis, and agenda-setting. In the digital age, this process has intensified because algorithms amplify certain narratives, prioritize emotionally charged content, and filter out alternative perspectives. As a result, consent is produced not through direct coercion but through the strategic shaping of the informational environment, influencing what people perceive as normal, legitimate, or socially acceptable.

The political experience of Zohran Mamdani in New York provides a real example of how manufacturing consent works within digital media ecosystems. Throughout his campaign, Mamdani-an outspoken progressive and advocate for Palestinian rights-was consistently framed by political opponents and powerful media as an “extremist” or an “unsafe” candidate. These frames were built intentionally to create distrust and fear among voters. Political action committees and lobbying groups spent money on targeted digital advertisements that plucked his pro-Palestine statements out of context, without mentioning his deeper legislative accomplishments and community service. This messaging is further amplified by algorithmic systems designed to surface highly emotional or polarizing content, which ensures that many voters saw these negative frames well before being able to consider Mamdani’s actual platform or policies.

This dynamic illustrates manufacturing consent in two ways. First, through the framing of Mamdani, media and political campaigns selected specific angles and repeated them to create a sense of consensus about his character. The process involved filtering and agenda-setting, where disproportionate attention would be paid to aspects of his political identity while others were ignored. Compared to attention given to his controversial foreign policy positions, for example, hardly any details emerged about his work on housing, economic justice, or community development. Digital platforms further entrenched this imbalance by amplifying content that aligned with pre-existing narratives at the expense of shaping voters’ perceptions to benefit entrenched political interests.

But the Mamdani campaign also reveals the limitations of manufactured consent. Alongside a coordinated messaging effort to discredit him, Mamdani was able to challenge these framings through grassroots organising, multilingual outreach, and direct communication with his constituents. His campaign engaged digital media to create counter-narratives, framing Mamdani as a community-grounded candidate deepening the cause of social justice. By speaking directly to voters in their native language about issues that were distinctly absent from the mainstream coverage, Mamdani broke up the informational environment built around him by his opponents. This is to say that his eventual victory indicates that manufacturing consent may strongly influence public opinion but is never absolute. When communities are engaged and offered sources of information outside elite framings, they may resist the dominant classes’ attempts to mold and shape political reality.

The case of Mamdani demonstrates how manufacturing consent works within digital politics through framing, agenda-setting, and algorithmic amplification. At the same time, it shows that informed communities, grassroots communication, and diverse media strategies can challenge and reshape dominant narratives.

References:

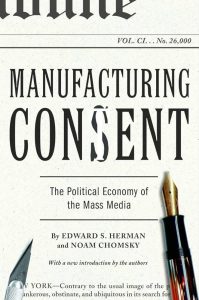

Chomsky, N. & Herman, E.S., 1988. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon Books.

Entman, R.M., 1993. ‘Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm’. Journal of Communication, 43(4), pp.51–58.

McCombs, M. & Shaw, D., 1972. ‘The agenda-setting function of mass media’. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), pp.176–187.

Couldry, N. & Mejias, U.A., 2019. The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Tufekci, Z., 2015. ‘Algorithmic harms beyond Facebook and Google: Emergent challenges of computational agency’. Colorado Technology Law Journal, 13(1), pp.203–218.

Image references:

https://share.google/images/AHvnWJLcIioF4Nrei

https://share.google/images/jPvExO1odgIfvawTN

Hi, it was really captivating to read about manufacturing consent theory through a Mamdani example. As you mentioned in your text, the campaign against Mamdani carries a certain ideology behind it, and makes people believe that he is an “unsafe” and “extremist” candidate, which proves that the 5 steps of manufacturing consent theory, through which information is presented to us and the algorithms of social media really make us believe in the ideology behind the message. But the same algorithms also provide people with an opportunity to change people’s perception and turn the situation around, as it was in the Mambani example, which shows us that even in these structured systems, there is always an opportunity to reshape opinions.