In today’s media environment, public opinion is often seen as an important foundation of democratic society. However, many theoretical and empirical studies show that the media is not fully independent. Instead, it is shaped by political, economic, and technological structures that create systematic bias. Herman and Chomsky’s (1988) “propaganda model” explains how mass media uses five filters—ownership, advertising, news sources, flak, and dominant ideology—to “manufacture consent” without direct censorship. These structural mechanisms help the media maintain existing power relations.

Although the model was created in the era of traditional mass media, research from the past ten years shows that its basic logic is still valid in the digital age, but now appears in new forms. Fuchs (2018) argues that platform algorithms, data capitalism, and the attention economy have become new filters. These mechanisms shift propaganda power from centralized news organizations to highly commercial technology platforms. At the same time, research on media capture shows that governments and business groups can influence news production through institutional channels such as control of advertising markets, media mergers, and regulatory pressure (Choi & Yang, 2021). A quasi-experimental study by Louis-Sidois and Mougin (2023) further finds that when media outlets are influenced by political or economic power, their reporting on corruption cases decreases significantly, showing that structural bias can be measured.

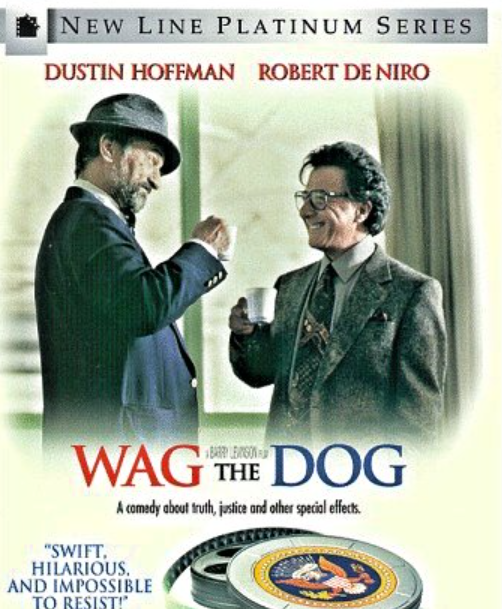

To examine how modern societies “manufacture consent,” I use a film I have watched as an example. The American movie Wag the Dog (1997), although fictional, shows in a satirical way how a government can use the media to shape public opinion. Its core logic fits well with the propaganda model. In the film, the U.S. president faces a scandal before an election. A political adviser and a Hollywood producer work together to create a fake “Albanian war.” Through professional storytelling, staged video, and control of the media agenda, they successfully shift public attention. The film clearly shows the five filters:

1:Ownership and power structures:

The war story is created by political advisers and the entertainment industry, showing how power and media production are connected.

2:Advertising and commercial dependence:

The film shows that the media needs “stories” to keep audience attention. War is a highly attractive story, illustrating how commercial interests shape news.

3:Source filtering:

Journalists depend on government sources and lack the ability to verify information, so official stories easily become “facts.”

4:Flak (response pressure):

The fake war story is emotionally powerful, so people who question it are pushed aside.

5:Ideological framing:

The fake conflict is presented as “protecting American values,” making the public more willing to support the story.

These mechanisms work together to make the “fake news event” become mainstream public opinion. Although the film is exaggerated, similar structural conditions exist in real life. Barnehl and Schumacher show through text analysis that in countries with media capture, news narratives systematically support the interests of those in power. In the digital platform era, algorithmic recommendation systems—such as models that prioritize user engagement—may further enlarge these biases, allowing certain narratives to quickly dominate public opinion.

Reference list:

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon Books.

Fuchs, C. (2018). Propaganda 2.0: Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model in the age of the internet, big data and social media. In J. Pedro-Carañana et al. (Eds.), The Propaganda Model Today (pp. 71–92). University of Westminster Press. https://doi.org/10.16997/book27.f

Choi, J. P., & Yang, S. (2021). Investigative journalism and media capture in the digital age. Information Economics and Policy, 57, 100942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2021.100942

Levinson, B. (Director). (1997). Wag the Dog [Film]. New Line Cinema

Hi Zhiyuan! I really enjoyed your post with the way you explained Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model so clearly and made it really easy to see how it applies today. I liked how you connected the five filters to Wag the Dog. I have never watched the film, but now I want to! You tell us that the movie is about a president facing a scandal before an election, and to protect him, an adviser and a Hollywood producer ‘work together to create a fake “Albanian war.”’ This easily links to the propaganda model, which is well put together. I like how there is a subheading for the five filters, making it easier for readers (like me) to read. You show how the theory is still applicable in the digital age. I also thought your explanation of ideological framing was super clear, making it easy to understand how public opinion can be shaped. Overall, your post did a great job of connecting theory to both film and real-life media examples.