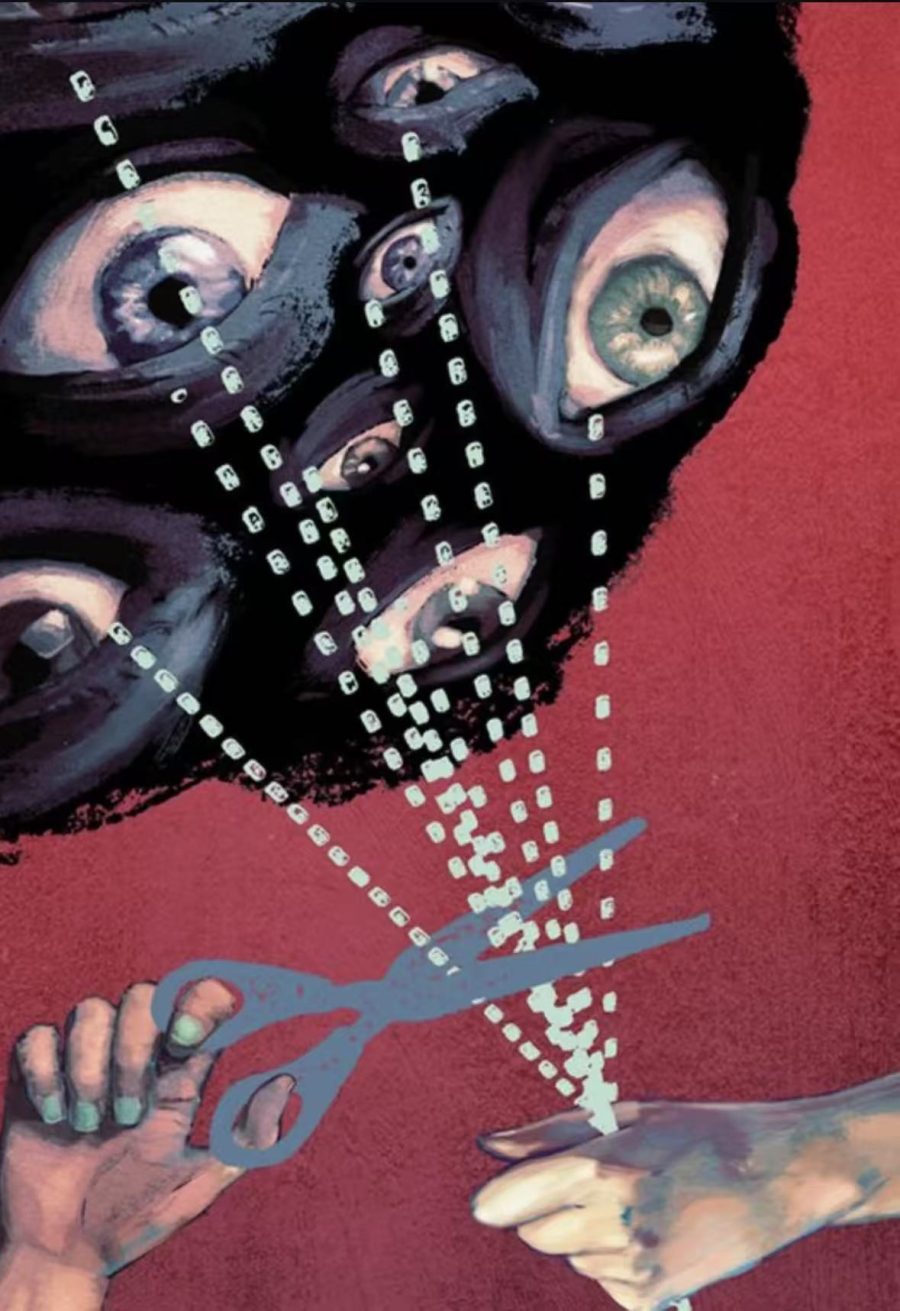

"The gaze from the male is a prejudice of invisible violence"

- I. Why do we need to repeatedly discuss “Male Gaze”?

The term “Male gaze” was proposed by Laura Mulvey in 1975, referring to the fact that film and television narratives, visual cultures and social structures often revolve around the viewing desires and perspectives of heterosexual men.

In other words: It’s not about how women view the world. Rather, it is about how the world demands that women be watched. Although this looks like an “old topic”, it is by no means solely related to film studies or feminism.

It is deeply embedded in:

- How do we evaluate a woman’s appearance

- 2. How do we understand the female body

- 3. The recognition, expectation and demand of women in society

- 4. Structural barriers to gender equality

- II. How Male Gaze Shapes Everyday Life

While women are being watched, they are also being regulated. In the cultural context of the “male gaze”, women are often expected to be “good-looking” but not “too proactive”, “sexy” but not “overstepping the line”, and “decent” but “knowing how to show off”. These standards may seem contradictory, but they have strong binding force. They are not set by women but by “viewers”.

2. Men are not malicious; they are just accustomed to taking the center stage

The core of Male gaze is not “bad men”, but:

The viewing perspective of men is defaulted to the mainstream perspective.

Therefore, in advertisements, variety shows, films and TV series, and social media, the image of women often tends to be more beautified, softened, sexualized and easily appreciated. The male image is shaped as: the actor, the narrative subject, the decision-making center and the driving force of the plot. This mechanism will profoundly influence discussions on gender equality, as “who is seen” as the “subject” often determines “who can speak out”.

- III. A Small Case Study: Lust, Caution and the Politics of Looking

To make the concept of “male gaze” more intuitive, we can look at an example.

In Ang Lee’s film “Lust, Caution”, Wang Jiazhi’s body, eyes, clothing and posture were all captured by a large number of shots, and these images made her the “subject of viewing”. Many early viewers also focused their attention on whether her body was “overly exposed”, whether she was “sacrificing herself”, and whether her “desires were genuine”.

These discussions themselves reflect the male gaze: The body and desires of female characters often become “issues” first rather than their actions, decisions or subjectivity.

Nowadays, the new generation of audiences have begun to ask in return: “Why can’t Wang Jiazhi have complex and contradictory desires?” “Why is active use of the body regarded as’ impure ‘?” ” “Why can men have depth, while women are labeled as’ problems’ whenever they have desires?” ”

This transformation clearly shows: The current understanding of gender equality is driving us to re-examine the male gaze.

- IV. Male Gaze vs Gender Equality: Why They Are Inseparable

1. Equality does not mean “men and women are the same”, but rather “women are no longer regarded as images”. The issue with the male gaze is not that “men are looking at women”, but rather that women are regarded as “the objects of observation”, while men are seen as “the subjects of action”.

In an unequal structure, women are often: more likely to be judged by appearance, more likely to be labeled, and more likely to be expected to “conform” to the viewing logic. When society begins to realize the injustice of this structure, it also starts to promote equal rights thinking: Can women freely define their own bodies? Can women not take beauty as their main value? Can women become the narrative subject rather than visual decorators?

And often the same gaze, why can’t it be inverted on a woman and applied to a man? The reason is simple: because the entire standard of the gaze was customized in a patriarchal society.

2. How can men participate in equality? It’s not about stopping to look, but changing how to look.

Eliminating the “male gaze” does not mean that men should “not look at women”, but rather: not objectify women. Do not simplify women to appearance and body. Not treating women as “default evaluators” in public Spaces; Not only do they accept the voices of beautiful women, but they also ignore the expressions of ordinary women.

This is a correction of the way of viewing and also a redistribution of the cultural structure. Today’s female viewers, female creators and female users are launching a counterattack with their cameras, pens and words. They engaged in discussions on physical autonomy on social media, female directors redefined the female subject, female audiences refused to be gazed upon and looked back at the gaze itself, gradually prompting society to reflect on aesthetic pressure. On the other hand, men should also start to reflect on their “accustomed perspectives”, because this “female look back” is precisely a redistribution of the male gaze. We still need to discuss male gaze because it is not a film theory but a cultural logic.It influences: how women understand themselves, how men treat women, how society distributes power and how equality continues to advance.

Women are not just being watched; they are also beginning to be watched. Women are not just objects; they also become narrators. And when we start to be aware of our “way of seeing”, we begin to redefine the “world being seen”.

Reference:

1. Rose, R. and Mulvey, L. (2016) Laura Mulvey : ‘Visual pleasure and narrative cinema’ 1975. London: Afterall Books.

2. Berger, J. (2008) Ways of seeing. London: Penguin. Available at: https://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=WestminUni&accId=9080556&isbn=9780141917986.

3. Mercier, E. (2025) ‘Exploring Everyday Slutshaming: The Role of Family and the Male Gaze in Reproducing Women’s Sexual Shame’, Sexuality & culture, 29(2), pp. 864–882. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10303-2.

Hey,

Thank you for your blog post on the male gaze, it was well structured and you managed to seamlessly tie it to contemporary media. You stated well that the male gaze can not just be reversed between a male and a female because the entire standard of the gaze was customised in a patriarchal society. It is fascinating how subconscious the impact of the male gaze is. Women start seeing themselves through this lens and confirming their behaviour accordingly, whilst men get reaffirmed in their predominant position ignoring to see the woman for something more than their bodies. I believe it is of utmost importance that we discuss the male gaze and point out its current existence in the advertising and entertainment field. To create a new reality, we must make more space for females to represent themselves in a desired way on screen. I also found it crucial how you stated the issue is not “bad men” but rather the role the male have to play in this which is shifting the default mainstream perspective. The male and female must both understand that neither one is worthy of being downgraded to just being an object of observation.

This cultural phenomenon needs to be closely looked at and discussed for actual change to happen within the industry. It is necessary to comprehend how the male gaze is feeding into already existing gender inequality and how it is shaping the upcoming generation of story tellers. This piece was insightful and had strong arguments to backup academic sources.

Great job! 🙂

Hey,This blog gives the “male perspective” a new vitality. It does not regard it as an old theory, but as an everyday and implicit cultural logic, just like Wang Jiazhi in Desire and Vigilance was simplified into her body before making a choice. I like that it avoids blaming “bad men”, but focusses on the patriarchal system that makes the male-centred perspective the norm. Its focus on “redistribution of perspectives” (realised through the counterattack of female creators and audiences) gives people a sense of hope, not just critical. This is not just a complaint, but a sharp and empartious call for us to re-examine how to evaluate women.