Before Jennifer’s Body even reached cinemas, audiences had already been trained to see women through a ‘lens,’ where it was normal to be oversexualised. In Erving Goffman’s book ‘Gender Advertisements,’ he states “under headings like “The Feminine Touch,” “Function Ranking,” “The Ritualization of Subordination,” “Relative Rank Size,” and “Licensed Withdrawal,” Goffman makes us see such observable phenomona in advertising,” whereby for example, “when a photograph or shaping… of men and women illustrates an instruction of some sort the man is always instructing the woman, even if the men and women are actually children that is, a male child will be instructing a female child” and “when an advertisement requires someone to sit or lie on a bed or a floor that someone is almost always a child or a woman, hardly ever a man” (p. 8). He shows that media repeatedly presents women as submissive, smaller, softer than men, and this leads to women being prejudged by viewers due to these advertisements showing how a woman should behave.

Even though these cultural expectations still affect women to this day and the male gaze, feminism helped challenge and expose them. First wave feminism, with the UK suffragettes, won women the right to have a political voice, aiming for equality with men, and liberty, as ‘female emancipation seemed the natural outcome of the Liberal goal of removing artificial restrictions, expanding individual opportunity.’ The Second Wave (1950s/70s) revealed how society confined women to domestic roles. Betty Friedman, in her book ‘The Feminine Mystique’ (1963), says “the feminine mystique says… the only commitment for a woman is the fulfilment of their own femininity.” Though, radical feminists saw men as the cause of the ‘construction of gender and sexuality that benefits men.’ Especially according to Simone de Beauvoir in ‘The Second Sex’ (1949), she exclaimed “one is not born, but rather, becomes a woman.” These movements opened up new opportunities and challenged entrenched stereotypes, though we were able to embrace ‘girliness’ as femininity can be embraced without being oppressive, according to McRobbie in ‘Aftermath of Feminism’ (2008). Feminism made it easier to express ourselves, but it didn’t erase the male gaze; it gave women tools to resist it.

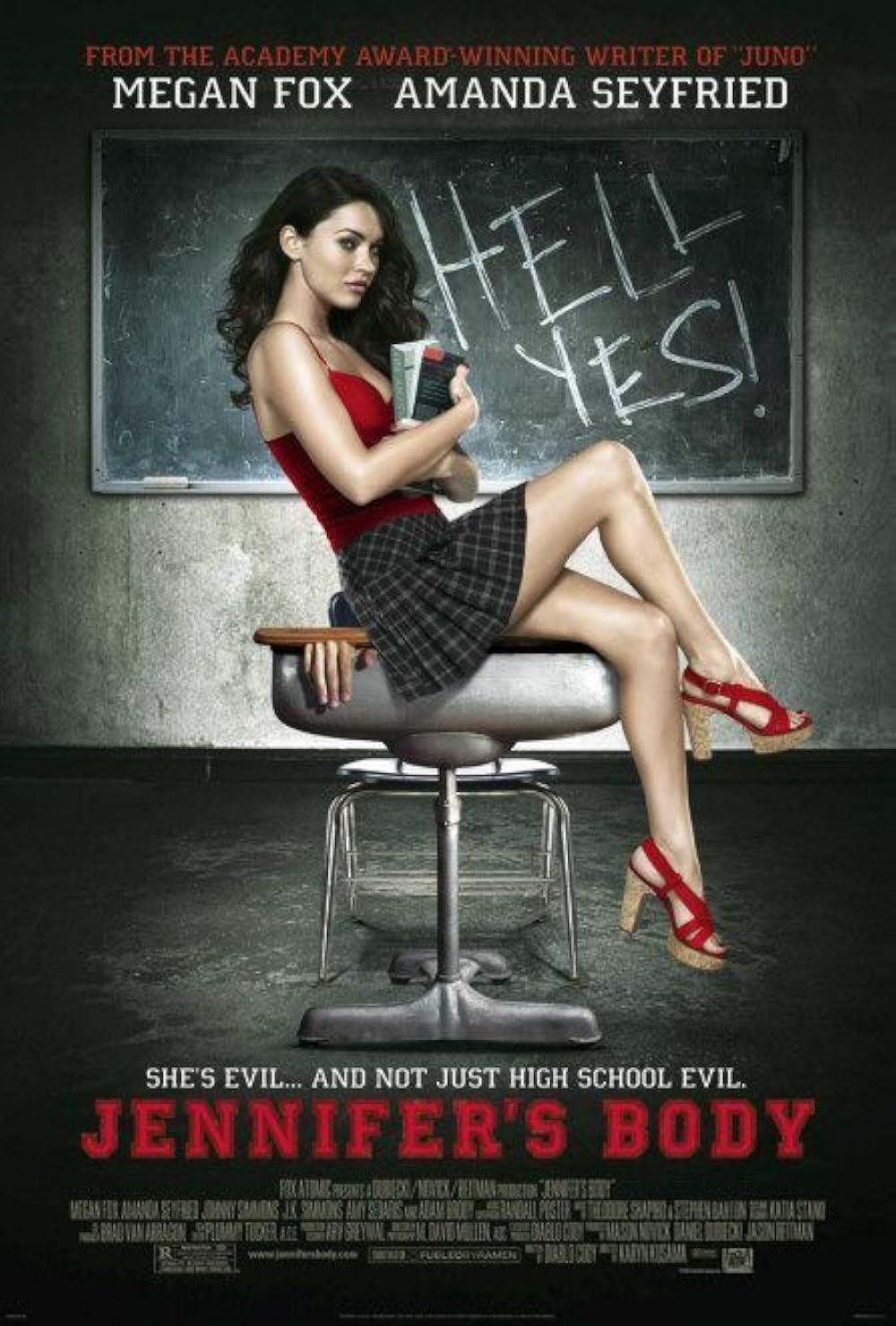

Laura Mulvey in ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975), discussed how Hollywood mainstream films are created in the eyes of male heteronormativity, and this takes place when “the audience is put into the perspective of a heterosexual male.” This means that women are “objectified,” meaning a person is viewed as a thing to be looked at or used, rather than as a fully realised human being with a personality and feelings. The audience is catered to men, which explains why, in Jennifer’s Body, the actress Megan Fox is often oversexualized, frequently wearing short skirts and tight tops throughout the movie. Regarding their advertisement, in one poster, Megan Fox wears a short skirt and clutches books to her chest, posed like a naughty schoolgirl, while another shows her with red lipstick, licking her lips suggestively. These images might have invited audiences to stare rather than think, shaping the perception of the film before anyone had even seen it, which might have led people to watch it for the wrong reasons. Even though, in the movie, it may seem it denies the male gaze, and possibly focuses on the queer gaze, where Jennifer and Needy passionately kiss, and there may have been connotations of them liking each other when they would be highly protective of each other, especially Jennifer. Also, stirring to the female gaze, when Jennifer says “no, I’m killing boys” when Needy asks if she is killing people. However, the lines remind us that this was written by a man. For example, Jennifer says things like “these things [breasts] are like smart bombs. You point them in the right direction, and…[it] gets real,” or “I’ll just play Hello Titty with the bartender.”

The male gaze still influences media, like in Jennifer’s Body, but the other perspectives are gaining more attention. The female gaze, for example, appears in Clueless, which centres around Cher’s life and how she gets into law school, even though the men, as well as her ex-fiance thought she couldn’t do it, and in The Wrong Paris, where the main character, played by Miranda Cosgrove, in one scene, stared at her potential love interest, who was shirtless, in slow motion, where she turns desire into her perspective rather than a male fantasy. In addition, the queer gaze provides women in the LGBTQ+ community with more opportunities to see themselves on screen and only cater to them. Today, the landscape has changed significantly since 2009, providing women and queer audiences with more opportunities to see themselves on screen. However, the male gaze remains a persistent influence in marketing, film, and social media, as exemplified by the introduction of OnlyFans.

References:

Jennifer’s Body (2009) Directed by Karyn Kusama. Toronto International Film Festival.

Goffman, E. (1979). Gender Advertisements.

History, L. (n.d.). Liberals and women · Liberal History. [online] Available at: https://liberalhistory.org.uk/history/liberals-and-women/

Friedan, B. (1963). The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

De Beauvoir, S. (1949). The Second Sex. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McRobbie, A. (2009). The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture and Social Change. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. London Afterall Books.

IMDb. (2025). Jennifer’s Body (2009) – Quotes – IMDb. [online] Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1131734/quotes/