When I first learned about Stuart Hall’s “encoding/decoding” model, it didn’t feel like a heavy theory at all. It actually felt more like someone finally explaining why people can watch the same video, hear the same joke, or read the same meme—and somehow walk away with completely different reactions. Once you start noticing it, you can’t unsee it.

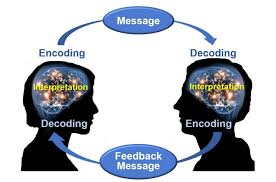

Hall’s idea is simple: every media message is encoded with certain meanings by the creator, but audiences decode it based on their own backgrounds, beliefs, and experiences. The interesting part is that these two sides don’t always match. And honestly, most of the drama on the internet today comes from this mismatch.

Take TikTok edits of celebrities as an example. The creator might intend to make a fun, light-hearted tribute video . But the comment section is full of people interpreting it in totally different ways: some see it as admiration, some as satire, and some accuse the creator of pushing a “parasocial relationship.” The video hasn’t changed—only the decoding has. This gap between what’s meant and what’s received is basically Hall’s theory playing out in real time.

What I like about this model is that it gives the audience more credit. Instead of seeing viewers as passive people who absorb everything, it argues that we actively make sense of media. Our cultural background, age, emotions, and even the time of day can affect how we decode a message. It explains why the same advertisement can look inspiring to one person and manipulative to another. Media isn’t a straight line—it’s more like a conversation where sometimes we misunderstand each other.

You can also see encoding/decoding clearly in brand communication. Think about a luxury fashion campaign that tries to look “edgy.” Maybe the brand encodes the message as creativity or rebellion. But audiences online might decode it as cultural appropriation or tone-deafness. The campaign fails not because the visuals are bad, but because the encoding completely misses how people will decode it in today’s social climate. This is where PR crises often start.

Even in daily life, the theory makes sense. A friend sends a short message like “ok.” For them, it’s just efficient communication. For you, it might look passive-aggressive depending on how you decode it. Hall didn’t write this theory for texting culture, but it accidentally predicts it perfectly.Forexample, when someone answers you in a chat, “mm-hmm” or “Oh”. The person who sent it may just be too lazy to type, casually respond, the coding is very simple. But the recipient often decodes it as: “are you impatient?” , “are you angry?” In an instant, the tone was imagined as a whole plot. That’s how a lot of fights start.

The most important takeaway for me is that communication is never guaranteed. Meaning doesn’t live in the message alone; it’s created between sender and receiver. For media students—and honestly anyone who posts online—it’s a reminder that we can’t fully control how people will interpret what we create. But being aware of this gap helps us communicate more responsibly and read media more critically.

Encoding and decoding isn’t just theory,Information is never a simple sentence, but something created by both sides. Everyone understands the same sentence with their own experience, emotion and background, so it is very normal to misunderstand.

Hiya, your post is really interesting, especially your point about people interpreting things in different manners, such as ‘ok’ being passive for some people, but normal to others. It’s simmilar for the thumbs up emoji, where some people will use it for everything as an easy response, but others see it as low effort and an attempt to end a conversation.